Gregory Bateson uses this term to describe progressive differentiation between social groups or individuals. For example, if two groups exhibit symmetrical behaviour patterns towards each other that are different from the patterns they exhibit within their respective groups, they can set up a feedback , or "vicious cycle" relation. For example, if boasting is the way they deal with the other group, and if the other group replies to boasting with more boasting, then each group will drive the other into excessive emphasis on the pattern, leading to more extreme rivalry, and ultimately to hostility and the breakdown of the system. (Steps towards an Ecology of Mind, p. 68) An arms race is another symmetrical form of schismogenesis.

sacred / profane

"Surrounded by a world full of wonder and vigour, whose laws man will never understand (though he may sense their existence and long to know them), a world which reaches him in a few interrupted chords that leave his soul unsatisfied, man conjures into being the perfection that he lacks, and, creating a miniature world where the cosmic laws, though restricted, may appear complete in themselves, he gratifies the cosmogonic instinct within him." (Gottfried Semper, Der Stil in den technischen und tektonishen K nsten.)

"During the Middle Ages, spatial relations tended to be organized as symbols and values. The highest object in the city was the church spire, which pointed toward heaven and dominated all the lesser buildings, as the church dominated their hopes and fears." (Mumford, "the Monastery and the Clock"

Mircea Eliade locates the primary spatializing impulse of architecture the demarcation of sacred from profane. He studies sacred space and the ritual building of human habitation as parts of the modality of sacred experience. For Eliade, the sacred and the profane are two modalities of experience, each with its own world. The former experience takes place in a sacralized cosmos, while the latter desacralizes the world in order to assume a profane existence. An echo of this distinction is to be found in the relationship between philosophy and poetry. (see truth )

In Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga, linking play to ritual, also emphasizes spatial separation from everyday life. (In a structuralist perspective, play and ritual are inverses of each other. eg. see time)

Read Morescience

"Science is any attempt to bring facts into logical order". B. Bavink (see explain / describe )

"Science is concerned with the formal correlation of properties, and with the development of theoretical constructs that most parsimoniously and usefully describe all known aspects of that correlation, without exception." (Edelman, p.138)

science / philosophy

For Ernst Cassirer, the tensions which emerged in the late nineteenth century between philosophy and science were between philosophy's "special task" to "oppose the intellectual division of labor" and the increasing difficulty of that task as a result of the constant increase in the specialization of the sciences. (see The Problem of Knowledge, Introduction)

Whitehead describes science as anti-rationalist (eg. medieval) and based on a naive faith in the relation between brute facts and general principles. Thus it has never cared to justify its faith or explain its meanings and has remained blandly indifferent to its refutation by Hume. For Whitehead in 1925, the stable foundations of physics had broken up and it was time for science to become philosophical and examine its own foundations -- specifically "scientific materialism."

In Order Out of Chaos, Prigogine and Stengers see the origins of modern science in a "resonance" or convergence between theological discourse and theoretical and experimental activity. (p.46) leading to the "mechanized" nature of modern science, that debases nature and glorifies God and man. Subsequently, triumphant classical science could say of God's place in the world system "Je n'ai pas besoin de cette hypothèse." (Laplace to Napoléon)

In What is Philosophy? Deleuze and Guattari characterize some of the differences between science and philosophy. For them, philosophy is "the art of forming, inventing, and fabricating concepts" (p.2), while the object of science is "not concepts but rather functions that are presented as propositions in discursive systems". (p.117) "Philosophy proceeds with a plane of immanence or consistency; science with a plane of reference."

Read Morescientific space

"I do not believe that there exists anything in external bodies for exciting tastes, smells, and sounds, etc. except size, shape, quantity, and motion." (Galileo Galilei, On Motion, p.48) When Galileo proposed his doctrine of subject and object and the distinction between primary and secondary qualities, he established the scientific prejudgement that the concept of space is of something geometrical and not differentiated qualitatively.

Newtonian "absolute space" was based on a realist conception of mathematics (see Jammer p. 95) To Newton, mathematics, particularly geometry, is not a purely hypothetical system of propositions...instead geometry is nothing but a special branch of mechanics. Newton's first law of motion, which links change in motion with force requires an absolute (or inertial?) framework. It requires a distinction between absolute motion and relative motion and links force to a change in absolute motion. For example, as the train pulls away from the station, the station may appear to be moving and it can be said that the station is in relative motion to the train, but the force is acting upon the train, and it is the train that is accelerating absolutely. Newton tried to establish an absolute frame of reference for the universe defined in relation to its center of gravity. (not necessarily identical with the sun) Absolute spatial movement and position could then be measured in relation to that point.

But is geometry an empirical or ideal activity? For Cassirer, the most radical removal of geometry from experience had already occurred with Euclid, which was already based on figures that are removed from all possibility of experiment. Not only the idealizations of point, line, and plane, but the idea of similar triangles, whose differences are considered inconsequential or fortuitous, and that become identified as "the same" mark an immense step away form ordinary perception.

Read Moreself-organization

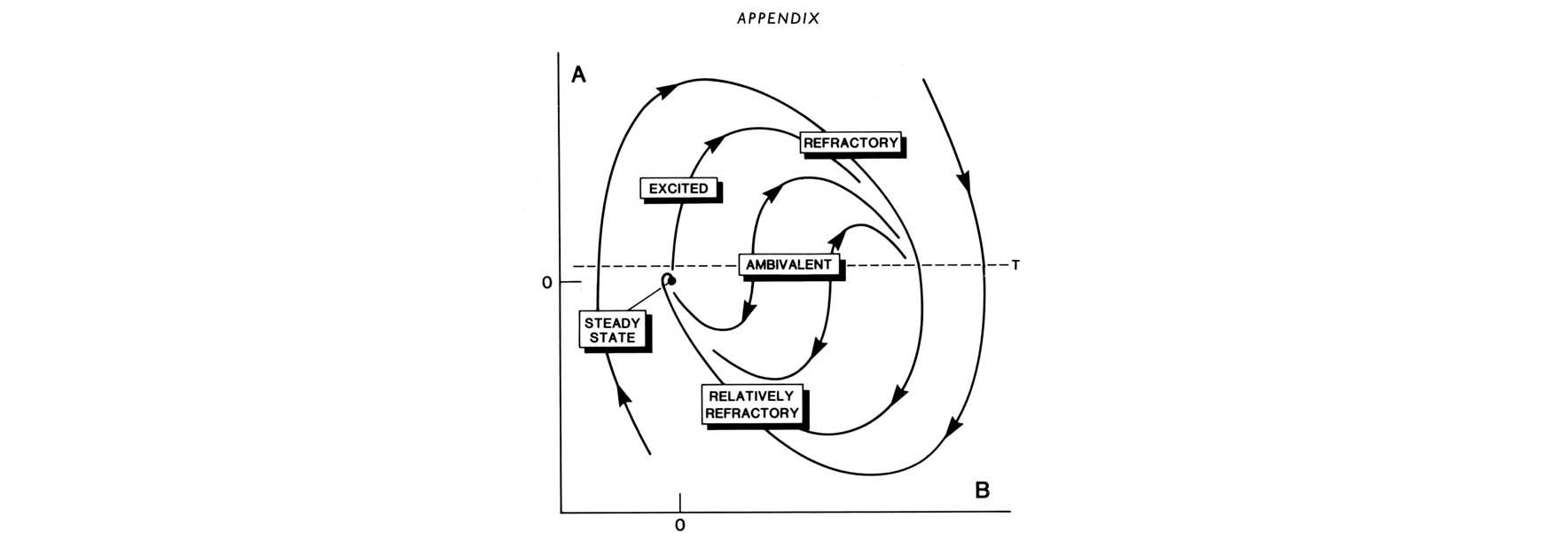

Self-organizing systems aquire new structure without specific interference from the outside. They exhibit qualitative macroscopic changes such as bifurcations or phase transitions. Stuart Kaufman calls this " Order for Free."Self-organization is the capacity of a field to generate patterns spontaneously, without any specific instructions. What exists in the field is a set of relationships among the components of the system such that the dynamically stable state into which it goes naturally -- what mathematicians call the generic (typical)) state of the system has spatial and temporal patterns. Fields of this type are now called excitable media. (see for example Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction.)

Read MoreSensitivity to Intial conditions

Sensitivity to Initial Conditions: An extremely small change in the initial conditions of a chaotic or non-linear system leads to extremely differing results. Any arbitrarily small interval of initial values will be enlarged significantly by iteration. This is the so-called "butterfly effect" in which the flapping wings of a single butterfly could theoretically make the difference whether or not a hurricane occurred in another place and time. (The title of a paper by Edward N. Lorentz was "Can the flap of a butterfly's wing stir up a tornado in Texas?"

sexuality

In its current usage, sexuality refers to the cultural interpretation of the human body's erogenous zones and sexual capacities. That the same two sexes occur in every society is a matter of biology...that there is always sexuality, however, is a cultural matter. Sexuality is that complex of reactions, interpretations, definitions, prohibitions, and norms that is created and maintained by a given culture in response to the fact of the two biological sexes.

Read Moresex / gender

On ne nait pas femme; on le devient -- Simone de Beavoir

At its simplest, the distinction between sex and gender is between a physical difference and a cultural difference. Gender is the mapping of socially and ideologically important distinctions onto biological differences between the sexes. (see also sexuality.)

The distinction between sex and gender becomes important in arguments that lean towards social constructionism, in which gender is given more attention, and is presumably more open to change, than sex. Feminism asserts that gender is a fundamental category within which meaning and value are assigned to everything in the world, a way of organizing human social relations. In a further twist on the relation between culture and nature, Brian Massumi calls gendering the process by which a body is socially determined to be determined by biology.

Read Moresimple location

"The characteristic common to both space and time is that material can be said to be here in space and here in time, or here in space-time, in a perfectly definite sense which does not require for its explanation any reference to other regions of space-time." (p.49)

Read Moresimulacrum

In "The Structuralist Activity," of 1960, Roland Barthes defines structure as a simulacrum of the object in which something new occurs: the simulacrum is "intellect added to the object," making something appear which remained invisible, or if one prefers, unintelligible. For Barthes, "Structural man takes the real, decomposes it, then recomposes it."

Read Moresimulation

"Simulation of any system implies a mapping from observable aspects of the system to corresponding symbolic elements of the simulation." (H. H. Pattee, "Simulations, Realizations, and Theories of Life", in Artificial Life) For Pattee, realizations are functional replacements. They are judged primarily by how well they function as implementations of design specifications. (Thus a building would be the implementation of a blueprint)

Read Moresmooth/striated

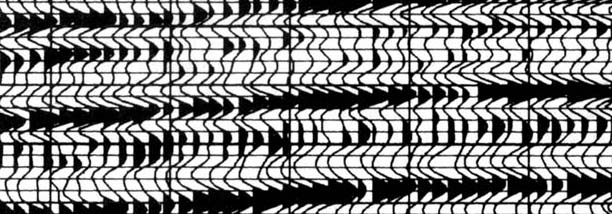

In Mille Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari distinguish between two kinds of spaces: smooth space and striated space. This distinction coincides with the distinctions they draw between the nomadic and the sedentary, between the space of the war machine and the space of the state appparatus. According to Deleuze and Guattari, smooth space is occupied by intensities and events. It is haptic rather than optic, a vectorial space rather than a metrical one. Smooth space is characteristic of sea, steppe, ice and desert. It is occupied by packs and nomads. It is a texture of "traits" consisting of continuous variation of free action. The characteristic experience of smooth space is short term, up close, with no visual model for points of reference or invariant distances. Instead of the metrical forms of striated space, smooth space is made up of constantly changing orientation of nomads entertaining tactile relations among themselves.

Smooth does not mean homogeneous, however, but rather amorphous non-formal (cf formless) in fact, striation creates homogeneity. Homogeneity is the limit-form of a space striated everywhere and in all directions. According to Deleuze and Guattari, striation is negatively motivated by anxiety in the face of all that passes, flows, or varies and erects the constancy and eternity of an in-itelf. Thus A Thousand Plateaus recounts an "extended confrontation between the smooth and the striated in which the striated progressively took hold."

space / place

"Give place, let the prisoner by; give place." -- the first English use of the word, according to the Oxford English Dictionnary

In the Physics, esp. book IV, Aristotle proposes a theory of place (topos) that rejects Plato's theory of space. The topos is a place of belonging. It is distinct from the body, which is defined by length, width, and depth. Yet there is a definite relationship of community or conflict between the nature of bodies and the nature of places: every physical element seeks "its" place, the place that belongs and corresponds to it, and it flees from any other opposed to it. For Aristotle "the motions of simple bodies (fire, earth, and so forth) show not only that place is something but that place has some kind of functional significance (potentia also force)" (cf. posture) although this power is not definable (like the forces of attraction and repulsion in modern physics)

Read Morespace

According to Sun Ra "Space is the place".

"The fascination which space seems to hold for philosophy is only equalled by the fascination which the idea of system holds for architects." (Christian Girard, Architecture et Concepts Nomades, p.72)

(cf. Roland Barthes' distinction between l'esprit de syst me and l'esprit syst matique .)

In this document, space is no longer considered unitary, as having a single essence, concept, or function. This is perhaps an indication of an outlook that is suspicious of the repressive ambition of a universal space which suppresses multiplicities, catastrophes, and incommensurabilities. One way to break with strategy is to fragment space. A typological approach to space in architecture, and a sensitivity to metaphor as crucial to theorization, indicate a move away from a singular concept of either space or theory.

The following taxonomy of spaces is a mixture of disciplinary divisions (art history, philosophy, etc.), technological divisions (writing, Cyberspace), territorial divisions (urban space), and subjective divisions (psycho-sexual, personal).

Read Morespace vs time

If Newton reduced the physical, objective, universe and Kant the metaphysical, subjective universe to the categories of space and time, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing performed the same service for the intermediate word of signs and artistic media. (Mitchell, p. 96) Lessing established a basic distinction between the spatial arts (such as painting.) and the temporal arts (such as poetry)-- the means or signs one"using forms and colors in space, the other articulate sounds in time." (Laocoön p.78) For Lessing, "These signs must indisputably bear a suitable relation to the thing signified.". Thus the true subjects of painting are bodies, i.e. objects or parts of objects that exist in space, and the true subjects of poetry are actions, that follow one another.

Read Moresocial space

"The paranoid person takes up too much social space" (Donna Haraway)

In The Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre reclaims space as a primarily social problematic. For Lefebvre, the proliferation of this and/or that space, eg. literary space, ideological space, the space of the dream etc. is a general consequence of of the concept of mental space (p.3) through the epistemologico-philosophical thinking of western Logos (in both science and philosophy). (see philosophical space ) Lefebvre unmasks this mode of thought as a powerful ideological tendency, expressing the dominant ideas of the dominant class, through the concept of abstract space.

The very proliferation of descriptions and sectionings of space is for Lefebvre an example of the endless division of labor within present-day society. Lefebvre sees spatial practice as the projection onto a (spatial) field of all aspects, elements and moments of social practice. (p.8) If he uses terms of language or contemporary theory, he is also at pains to recontextualize them as produced by a social subject. For example, he believes that a coded language (of space) may be said to have existed on the practical basis of a specific relationship between town, country and political territory, a language based on classical perspective and Euclidean space, and that that system collapsed in the twentieth century. But, he adds, if spatial codes have existed, each characterizing a particular spatial/social practice, and if these codifications have been produced along with the space corresponding to them, then the job of theory is to elucidate their rise, their role, and their demise. (p.17)

The task is thus a dialectical one, and both things in space and discourse on space do no more than supply clues to this productive process which subsumes signifying processes without being reducible to them. (p. 37) (see also representation)

Read Morespecies

why are there so many different kinds of animals?

All told, there are somewhere between two million and thirty million species of animals and plants alive on the planet today, and something like a thousand times that many species have evolved, struggled, flourished, and gone extinct since the Cambrian explosion. (The Beak of the Finch) And the great question of evolution is, Why? How do the lesser differences between varieties grow into the greater difference between species?

For Darwin, natural selection supplies the principle of divergence and tends to make nature "more & more diversified." Darwin realized that two varieties living side-by-side are thrown into competition, and unless one variety dominates and drives the other to extinction, the selective pressures will eventually move the varieties apart . Natural selection will lead to adaptive radiation -- the mutual adaptation of two neighbors to the pressures of each others' existemce. The occasional individuals with some character that sets them slightly apart -- that find a different seed to eat, a different nook or niche, will tend to flourish and so will their descendents. Over generations the varieties will move so far apart that competition will slack off.

Read Moresocial construction

For the founder of modern sociology, Emile Durkheim, "The determining cause of a social fact should be sought among the social facts preceding it and not among the states of individual consciousness."

At its most extreme, Social constructionism could be called "absolute relativism."

In The Social Constuction of What?, Ian Hacking analyzses the usage of the term "social construction" in a number of different contexts, from child abuse to quarks. Hacking distinguishes between "interactive" and "indifferent" concepts of "social construction." The former are drawn primarily from the social sciences, where the development of a concept in a matrix of institutions and practices, can effect changes on its very "object," particularly if the term is being applied to conscious human subjects. Hacking differentiates those interactive usages from the application of concepts of social construction to "indifferent" objects, such as physical particles. Presumably, "quarks" are indifferent to the names and concepts applied to them. According to Hacking, quarks themselves (the objects and not the concepts) are not constructs, are not social, and are not historical. (p.30)

Hacking acknowledges the "liberating" effects of the idea of social construction, (for example in gender issues) especially in helping "raise consciousness." He formalizes the arguments of social construction thus: (p.6)

(0) In the present state of affairs, X is taken for granted, appears to be inevitable.

(1) X need not have existed, or need not be at all as it is. X, or X as it is at present, is not determined by the nature of things; it is not inevitable.

Arguments proceeding from (1) often go further and urge that:

(2) X is quite bad as it is.

(3) We would be much better off if X were done away with, or at least radically transformed.

In developing his catalog of examples, Hacking also categorizes the intensities of commitment to constructionism, ranging from the historical to the ironic, the reformist or "unmasking" attitude to the rebellious or revolutionary.

Hacking himself believes that something can be both socially constructed and real, and seems unimpressed by critiques of science, especially the physical sciences, that use the term of "social construction." Yet he is careful to acknowledge that the directions of scientific research reflect social values. For example, he realizes that one must ask the question as to how much the tradition of science and technology in the West is fundamentally affected by the desire to create weapons.

One cannot easily imagine Francis Crick to be very sympathetic to the idea of social construction. But in describing vision, Crick emphasizes the constructive aspect of the process, of vision as active interpretation.

Is there a relation between the claims of social construction and the the presumably scientific observation that "what you see is not what is really there; it is what your brain believes is there"?

style

Inherent to the concept of style is an idea of historical necessity. A true style, like the Baroque of the seventeenth century, is not copied from a previous epoch, but arises out of some structural necessity, out of the manifest needs of man and society. "Style is, above all, a system of forms with a quality and meaningful expression through which the personnality of the artist and the broad outlook of a group are visible." (Meyer Shapiro, Style, in M. Philipson Ed., Aesthetics Today, p.137) (cf morphology) Style is an essential object of study for the historian of art. For the synthesizing historian of culture or the philosopher of history, style is the manifestation of the culture as a whole, the visible sign of its unity. The style reflects or projects the "inner form" of collective thinking and feeling.

Read More