More on the Model: Building on the Ruins (2020)

In 1976, the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies mounted an exhibition entitled Idea as Model. Paul Goldberger in The New York Times would complain of the exhibition that, “What is most disturbing is that there is no attempt, either through choice of exhibitors or through any sort of accompanying text, to discuss the whole question of models and their role in the process of making architecture.” The publication of Idea as Model (1982) would come after the fact, as a retrospective catalogue, with essays by Richard Pommer and Christian Hubert.

1981 Cover of Idea as Model, IAUS catalogue, 1981, with 1976 collage by Michael Graves tipped in.

In my desultory manner, I have been preoccupied with models ever since perching at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS) in New York, over the course of the 1980s. The catalogue essay I wrote at the time, “The Ruins of Representation,” along with a brief revisionist postscript written some years later and published in the Dutch Journal Oase, presented in concentrated form my interest in the expressive registers of architectural models, especially their dual functions as representations and actual objects, in the desires that they embody, and some of their underlying ideological functions in the rhetoric of postmodernism, with its penchant for historical pastiche.[1]

Christian Hubert, “Cuber(t), an Architectural Folly”, Computer image, 1983. Courtesy of the author. This early computer image of a future form of architectural folly incorporates a figure from Poussin, the Lissitzky Lenin Tribune project, and a quote from the intellectual historian Hayden White, to evoke an imaginative experience of cyberspace. Published in: B J Archer, Ed., Follies: Architecture for the Late Twentieth-Century Landscape, 1983. Exhibited at: Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, 1983.

I have primarily used my training as an architect as a springboard for intellectual inquiry, especially at the IAUS, and for creating environments for artworks, for artists, and exhibitions in my design work. More recently, I have been working on metal sculptures out of stainless steel. My creative and critical work share implicit affinities that are not always visible, and sometimes they only make sense to me after the fact.

[1] Christian Hubert, “The Ruins of Representation”, in Idea as Model, Rizzoli 1981, pp 16-27

LEFT: Transitional Object a, sculpture, Christian Hubert (2020). Courtesy of the author, with thanks to Madeleine Lord for her help and support. Paul Goldberger sought to differentiate architects from both painters and sculptors. He claimed that good architects are not sculptors, for architecture is concerned with the creation of interior space, whereas sculpture is pure form, although Frank Gehry’s work undermines that distinction. This sculpture, one of a series, suggests a similar ambiguity. Considered as a transitional object, a developmental concept developed by Donald Winnicott, it resists answering the question of whether it was found (in the world) or made up instead.

RIGHT: Christian Hubert “Inner Landscape (blue)”, stainless steel sculpture, 2019. Courtesy of the author. The play between representation and objecthood has been of explicit interest in painting and sculpture. Following the directions indicated by Picasso's guitar, which translated Cubist syntax into actual space, a number of works have situated themselves at the bounds of pictorialism and objecthood, locating the concerns of art at a crossroads of painting, sculpture, and architecture. This painted stainless steel piece occupies a similar niche.

Most models today are more concerned with the future than the past than they were at the time of that essay, and they employ techniques that have developed in the interim – especially digital technologies. One indication of the transformative effects of the digital has been a change in the defining features and ontological status of the model. The model’s physicality previously enabled it to function as both object and representation, and to define a space between two and three dimensions. But today, that physicality has waned in importance. The physical model has become more of a by- product than it once was. A 3D model produced from a digital file -- whether milled, rendered, integrated into the world of a game -- or even used to fabricate full-sized building parts -- remains primarily an expression of its digital instructions. It can convincingly simulate or instruct, but one source of its aesthetic criticality has been undermined. It doesn’t really matter if the model is a physical object today. It is the scenario expressed through the model that has become primary, and the goal of modelling a process has taken the place of modelling a product.

Worldmaking

Today, the concept of worldmaking subsumes the idea of the model, which has become an agent of the projective imagination. What worlds do these models build and occupy? Are they a source of hope or fear? What is the role of nature, as human culture has come to consider it, in those worlds? A deep ambivalence informs most of these models. They face the future with a mixture of optimism and dread. They are also meant to directly affect the course of events. Future-oriented models are reflexive, in the sense of creating feedback loops that change perceptions of reality, and in that sense, they are meant to change reality itself. They move beyond representation, with the goal of setting out possible worlds; some leaning towards forms of utopia, others toward dystopia.

Artist unkown, Photograph of float of Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, Leningrad, 1925. The model purports to present architecture, not represent it. Unlike the signs of language, whose signification is primarily a matter of arbitrary convention, the relation of the model to its referent appears motivated, in the sense that it attempts to emulate or approximate the referent. Here, the model is defined by its performative function, as a harbinger of a new utopian society. This simplified model (of a model) was carried through the streets of Leningrad in 1925. Joseph Stalin may have been on the tribune. (image courtesy of Maria Elizabeth Gough, Harvard University).

Although the term has not been formally adopted by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), the current period in Earth’s history is informally known as the Anthropocene Epoch, to describe the period in Earth’s history when human activity started to have a significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems. The concept of the Anthropocene gives humans planetary roles and responsibilities. The term is meant to be scientifically descriptive, but it inevitably entails ethical responsibility for its consequences. On the one hand, it acknowledges the defining role of humans: they have become forces of nature. On the other hand, it implicates humans in processes that they do not fully understand and cannot really control. As global “apex predators”, humans themselves are at risk from the environmental stresses they have caused or exacerbated, such as rising sea levels, the fragility of human food chains, water shortages, and the possibilities for global pandemics. In this sense, “worldmaking” is not a metaphor. It is a literal obligation, and not just to humanity. It requires imagination, but not in the form of wishful thinking.

We have already proclaimed the Death of Nature. Perhaps it isn’t dead yet (we would be too...), but what a job humans have done damaging it! Humans are making a world inhospitable to most species and increasingly to themselves. While they have succeeded in making planet Earth support a greatly increased human population, with significant gains in human standards of living, this achievement seems increasingly fragile. The bills are coming due, and the costs to other species and to habitats unbearably high.

The dreams of new worlds seem to coincide with the imminent collapse of the old one, and the new “desire” of the model, as expressed in worldmaking, is to be instrumental in creating these new worlds, to promote a reflexive reality, informed by hopes and fears that motivate its dynamic force. In this sense, models have become performative. They not only point to the future, but lay claim to building new worlds (even fictional ones), in the full awareness that those will not necessarily be improvements on the existing ones unless humans become stewards of life on earth.

There are two main ways in these reconfigurations of reality, technique, aesthetics, and natural processes can inform one another. The first is an explicit ecological and social agenda, in which life in every form is understood as process, in which humans, their technologies, other species, and the planet are all stakeholders. The second is the project of enabling human inquiry and design to work symbiotically with other agents – other processes or other species. The current task of models is to incorporate those parallel strains, to embody their potentials, and to function as “models” in the sense of exemplars.[1] A wide range of exemplars is available today. These include hybrid life forms – chimeras combining organisms and human technology, or new subjects such as networked symbiotic organisms – forests, lichens, slime moulds etc. – that move beyond concepts of the individual or population.

Worldbuilding

Like many boys his age, a young man in my immediate family (call him A.) has spent long hours online playing computer games. It is tempting to call this an addiction, but I feel that this would be ungenerous. It is certainly a time sink, though, and he seems to inhabit a parallel world, in which he socializes with friends he has never met, even to the point of actually rescuing one of them who had taken steps to kill himself. Over the years A. has played a series of games, from Minecraft, which definitely involves “worldbuilding”, to Total War. Minecraft is explicitly structured around making worlds, both on the individual and community level, and it is endlessly modifiable. The game is a small step away from architectural modelling programmes like Sketchup, and in turn, it has modified the way the newer generations perceive architecture. A. claims, with some truth, that he has learned a lot about military history in Total War, in its many iterations, as the game seems to have been meticulously researched. Games such as this provide vivid experiences of other times and places. In an application to college, he submitted an essay that involved participation in the 19th century Greek war of independence, which he was able to describe in convincing terms, due at least in part to his first person game experiences.

In his extraordinary novel, The Overstory, which focuses on the life of trees and humans who value and communicate with them, Richard Powers describes a brilliant game designer, crippled in childhood from falling out of a tree. In the book, this genius coder develops a highly successful multi-player world game, called Mastery. His project managers, who have become “boy millionaires” in the process, think he is crazy when he suggests incorporating “the marvelous world of what is happening underground, which we are just starting to learn how to see.” They insist you can’t make a game out of plants, “Unless you give them bazookas.” His response is to ask “Why give up an endlessly rich place to live in a cartoon map? Imagine: a game with the goal of growing the world, instead of yourself.” [1]

I am reminded of the confusion between the map and the territory in the Jorge Luis Borges quote from “The Ruins of Representation”.

...In that Empire, the craft of Cartography attained such perfection that the Map of a Single province covered the space of an entire City, and the Map of the Empire itself an entire Province. In the course of Time, these Extensive maps were found somehow wanting, and so the College of Cartographers evolved a Map of the Empire that was of the same Scale as the Empire and that coincided with it point for point. [2]

Both examples are doubly fictional: a hypothetical game described in a work of fiction, and a spurious history ascribed to a fictional author, but the “worldbuilding” impulse remains unmistakable, and they express the same priorities that I have been arguing for here. Even the ambiguities of the “real” and the “virtual” recall the arguments of “The Ruins of Representation”.

Models have become increasingly anticipatory in nature, not as simple representations, but as predictive scenarios. In this sense, they contribute to world making. In the Anthropocene era, they describe the world that humans are in the process of making by extrapolating from current trends in environmental degradation. For the most part, they are adaptations to conditions increasingly hostile to human life, in a hot, dry, and dangerous planet, or on other planets altogether.

Worldmodelling

“Nature everywhere speaks to man in a voice that is familiar to his soul.” Alexander von Humboldt. [1]

If worldmaking aims at making and remaking the world, and worldbuilding seeks to develop alternate or imaginary worlds, worldmodelling is a search for insights into the workings of the world as we find it. Apparent triumphs of the technological imagination are taking place against a backdrop of anxiety about species’ extinctions and threats to the survival of human life. The title of a sobering account of a time after humans, The World Without Us,[2] purports to give a scenario of the pace of change that would result from the end of human intervention in the landscape, and the process of natural self-healing that would take its place. In cities like New York, during the Covid pandemic, we have recently caught a glimpse of that world, when birds are heard singing in the early morning instead of the rumbles and honks of automobiles, or when the sky returns to a bright blue without the haze of pollution.

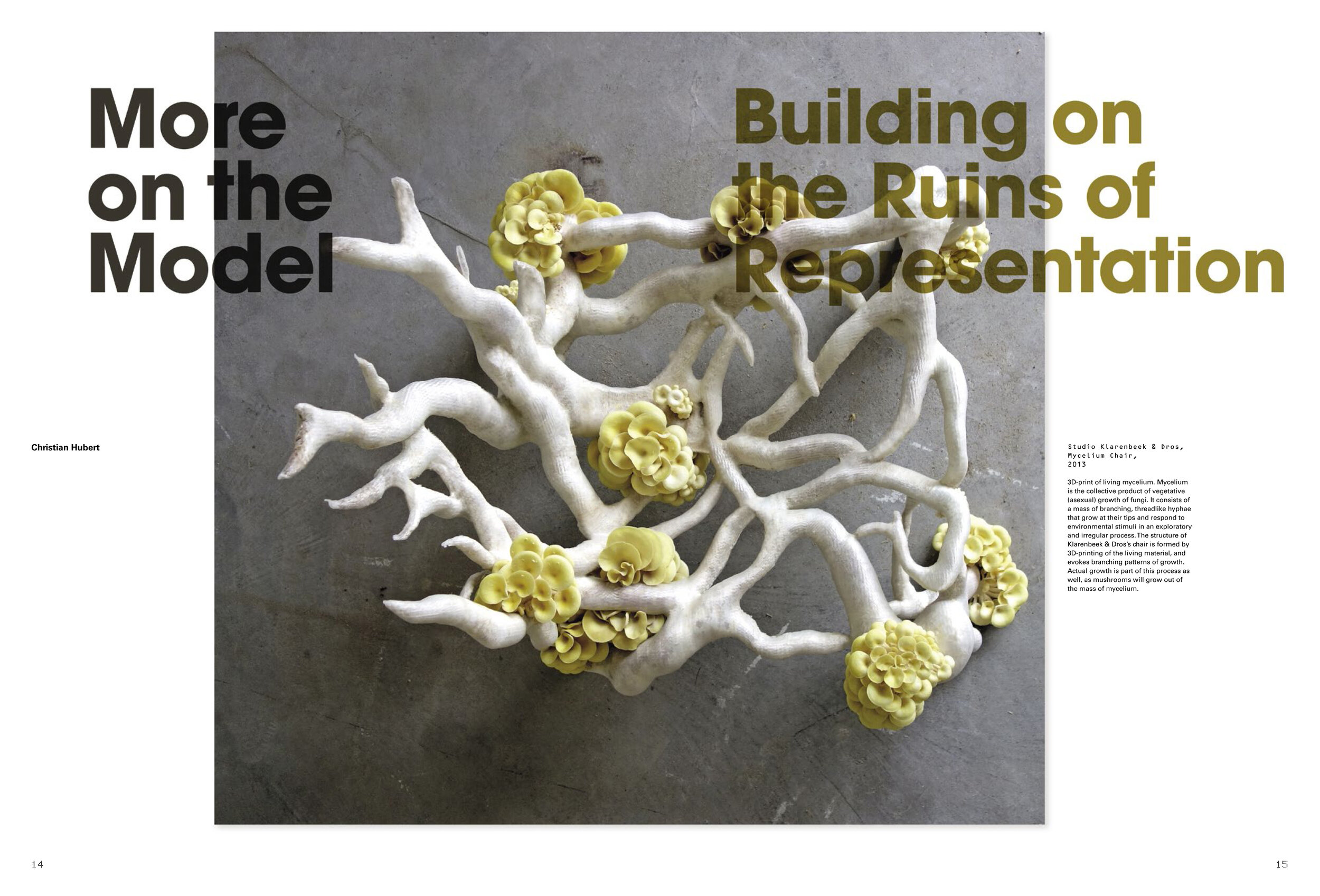

Even as the natural world is under attack, profound new insights into its workings are suggesting “models” – in the sense of exemplars – for creative thought and design. The potential for new forms of modeling are not limited to addressing environmental issues. They also open up new modes of aesthetic imagination. Biological evolution, for example, has primarily been described in terms of (functional) adaptation, and judgments of beauty have generally been considered the exclusive province of humans. Aesthetic judgment, especially since the Enlightenment, has been identified with a harmony between the world and the workings of the human mind. But in The Evolution of Beauty, Richard Prum convincingly documents the “transformative power of female mate choice” on the appearance and behaviours of male birds. For Prum, following Darwin, “Beauty Happens” (as the animal perceives it )… whenever the social opportunity and sensory/cognitive capacity for mate choice has arisen. [3] New opportunities for symbiotic design and co-production with other species are emerging, such as Neri Oxman’s and the MIT Mediated Matter group’s work with silkworms, or the mycelium chair by Eric Klarenbeek , although a delicate creative balance between humans and other species needs to be established in every case. As humans, we need move away from our species-centric views of nature and our urge to control, in order to better understand how we are part of the world.

LEFT: Mycelium is the collective product of vegetative (asexual) growth of fungi. It consists of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae that grow at their tips and respond to environmental stimuli, in an exploratory and irregular process. The structure of Eric Klarenbeek’s mycelium chair is formed by 3-D printing of the living material and evokes branching patterns of growth. Actual growth is part of this process as well, as mushrooms will grow out of the mass of mycelium.

RIGHT: The Bombyx mori silkworm starts by spinning a scaffolding structure that it triangulates, while attaching its fibers to its immediate environment. Over the course of spinning this scaffolding, it will also close in onto itself to begin to construct its cocoon out of a single fiber. The fabrication process of the Silk Pavilion emulates the process of the silkworm through both robotic techniques and management of live silkworms. The process consists of two phases: creating of the “scaffold” by a robotic arm, and subsequently deploying thousands of silkworms to spin a secondary silk envelope. A rotating jig ensures that they spin a flat surface. The project authors, Neri Oxman and the Mediated Matter Group, describe the Silk Pavilion as a case study for biomimetic digital fabrication.

Alexander von Humboldt claimed that the “netlike, entangled fabrics” of nature appear gradually to the observer. [4] According to Merlin Sheldrake, what was a metaphor used to describe the “living whole” of the natural world is literally the case in mycorrhizal (fungal) networks, in which trees and fungi are inextricably entangled. Science and technology have led to new metaphors in turn, such as “the Wood Wide Web” – coined more or less at the same time as mathematical tools were being developed for the study of networks, and when the World Wide Web seemed to afford new utopian opportunities. In a humorous passage, Sheldrake wonders if humans tend to give ontological priority to trees over fungi, a “plant-centric” [5] view of fully symbiotic relationships.

Pleurotus mushroom growing from Sheldrake’s book, allowing him to “eat his words”.

A poignant slogan of the counterculture was “Utopia Now!” (today a reference a clothing brand – most likely trademark protected), and it is only a small step from the study of fungi to calls for “changing one’s mind” through psychedelics. A recent book by Michael Pollan, a convert to benefits of psychedelics, documents lasting changes to personality occasioned by consuming “the flesh of the gods”, including the sense of being one with nature, and the feeling of “co-creatureliness”.[6] This renewal of interest in the benefits of psychedelics has given new hope to wishful thinking, which lies beyond the scope of this brief essay. It remains an open question as to whether subjective experiences of “one-ness” with nature can lead to effective attunement between nature and culture, but the key question for humanity is whether it can integrate its increasingly powerful capacity to control the earth with its ethical responsibility for the future of life and a symbiotic and poetic relation to other life forms. Whether the Anthropocene will turn out to be a moment of creativity or a catastrophic one remains very much an open question. Performative models will serve as signposts along the way.

Christian Hubert, New York, 2020

Christian Hubert, Sketches for a Kelp Oasis, (2020). Courtesy of the author. Worldmodelling emerges as the world starts to collapse. It is a coping mechanism and a logical reaction at the same time. Only through speculation at the scale of the world can solutions to ecological, climate, and socio-economic catastrophes be considered. This proposal for an “Ocean Oasis”, proposes a design for an educational kelp farm and wellness center, that offsets the warming and acidification of the ocean at a local level

Christian Hubert , New York 2020

ENDNOTES

[1] See Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,

[2] Richard Powers, The Overstory, W.W. Norton (New York), 2018. pp. 412-413.

[3] J. L. Borges, “On Exactitude in Science”, in A Universal History of Infamy, Penguin Books (London), 1975, p.325.

[4] quoted in Andrea Wulf, The Invention of Nature, Alfred A. Knopf (New York), 2015, p.54.

[5] Alan Weisman, The World Without Us, Saint Martins Press (New York), 2007.

[3] Richard O. Prum, The Evolution of Beauty, Doubleday (New York), 2017, pp. 72, 119-120.

[6] Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life, Random House (New York), 2020, p. 149, and note page 268.

[7] ibid, pp. 160 ff.

[8] See Michael Pollan, How to Change Your Mind, Penguin Press (New York), 2018, Chapter 2.