Henri Focillon describes the relationship between the hand and the tool as a human familiarity, whose harmony is composed of the subtlest give-and-take, not just a matter of habit. (The Life of Forms in Art, p109.) "Once the hand has need of this self-extension in matter, the tool itself becomes what the hand makes it. The tool is more than a machine. " The "exact meeting place" of form, matter, tool, and hand is the touch.

Read Moretop down / bottom up

Proponents of A-life have argued for the superiority of bottom-up thinking over top-down as being more like the way life works -- based on interactions of populations without a "master plan."

Read Moretopos

The Greek word topos meant literally a place, and ancient rhetoric used the word to refer to commonplaces, conventional units, or methods of thought. For the Ancients, particularly for Aristotle, topoi were rubrics with a logical or rhetorical value from which the premisses of argument derive. In the Renaissance, topics became headings that could be used to organize any field of knowledge.

Read Moretransclusion

The idea of quoting without copying was called transclusion by the designers of Ted Nelson's Xanadu operating system. The most innovative commercial feature of the hypertext system was a royalty and copyright scheme for use without copying. Whenever an author wished to quote, he or she would use transclusion to " virtually include" a passage by pointing to the original. (This function operates like the "make alias" command on the macintosh. It is a pointer rather than a copy.) Literal copying would be forbidden in the Xanadu system. A fee could be charged for transclusion, every time an individual work was being read or quoted.

Read Moretree

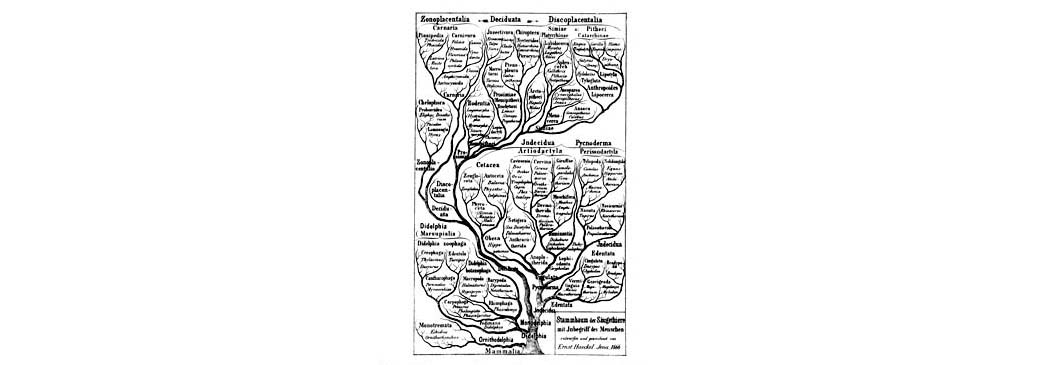

The image of the tree, of branching phylogenies, has come to underly all our thinking about organisms and evolution. It is a "canonical icon" whose influence can be described as an " unconscious hegemony."The hierarchical structure expresses the pattern of branching speciation, of successive, unending, natural wedging through natural selection which forms the "tree of life." The tree combines the "ladder" of evolution, from lower to higher lifeform -- and with man at the top -- with the "cone" of increasing diversity. (Steven Jay Gould in Hidden Histories of Science) As Gould points out, the latter is factually incorrect. The Cambrian explosion was the moment of greatest diversity. The former is, of course, an anthropocentric bias.

Read Moretruth

Plato and Euclid developed an indissoluble partnership between geometrical and philosophical ideas of truth. The Platonic concept of the theory of ideas was possible only because Plato had continually in mind the static shapes discovered by Greek mathematics. On the other hand, Greek gemetry did not achieve completion as a real system until it adopted Plato's manner of thinking. (see Ernst Cassirer, The Problem of Knowledge.) The concepts and propositions that Euclid placed at the apex of his system were a prototype and pattern for what Plato called the process of synopsis in idea. What is grasped in such synopsis is not the peculiar, fortuitous, or unstable; it possesses universal necessary and eternal truth. (see transcendence / immanence) This is the space of universal truth that differs from the spaces of a kind of truth that funtions only in the context of local pockets, a truth that is always local, distributed haphazardly in a plurality of spaces, with regional epistemologies.

Read Moreunconscious

How can the unconsious be known? (in German, it is the Unbewusste, the unknown ) Can it only be diagnosed, inferred through its symptoms in parapraxis? Can ideas and memories be effective yet unavailable to consciousness?

Read Moreutopia / heterotopia

In an article entitled "Other spaces; the principles of heterotopia", Michel Foucault looks at spaces which are in rapport in some way with all the other arrangements of space in a given society, but yet in some way contradict them.

Read Moreunity

For Kant, the categorial principle of unity is a requirement for the very concept of nature. As he puts it in the Prolegomena to the Critique of Pure Reason, "nature is the existence of things, considered as existence determined according to universal laws." For Kant, the idea of God serves to symbolize or "schematize" the highest form of systematic unity to which empirical knowledge can be brought, the purposive unity of things. (B714)

According the Kant, the idea of space, a priori, is that of a unity. In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant defined space as "the form of all phenomena of the external sense, that is, the subjective condition of the sensibility, under which alone external intuition is possible." (p.26) (For Ernst Cassirer, the recognition of non-Euclidean geometries seemed to mean renouncing the unity of reason, which is its intrinsic and distinguishing feature." (see scientific space )

In the Critique of Judgement, he realizes that the absolute conditions of experience are not enough, and that experience depends on our ability to arrange the particular laws of nature according to the idea of a system. The empirical unity of nature in all its diversity is not identical with the categorical one, not constitutive of our experience, but a regulative one.

It is the business of our understanding to introduce unity into nature. For a scientist to succeed at his task, he must assume that something corresponding to this unity actually exists in nature to be discovered.

Read MoreVirtual Reality

VR is a simulation of embodied presence, based on a feedback loop between the user's sensory system (see proprioceptive ) and the cyberspace domain, using real-time interactions between physical and virtual bodies. It relies on the assumption that the senses function as they always have, even in the face of perceptual inputs that have been drastically altered. Yet one of the principal "allures" of virtual reality is its promise to leave the body, on what Elizabeth Grosz calls "somatophobia."

Read Morevirtual

"Reality is that which is, 'virtuality' is that which seems to be." (Ted Nelson)

Traditionally, for something to be virtual meant that it possessed the powers or capabilities of something else. In the late 1950's, scientists developed what they called "virtual computers" -- machines quick enough to handle several users sequentially while giving each user the impression of being the only one using the computer.

In this same sense, a propagating information structure, such as a "glider" in the "game of life" (see cellular automata) is a virtual machine. For Christopher Langton, behaviors themselves can constitute the fundamental parts of non-linear systems, virtual parts, which depend on non-linear interections between physical parts for their very existence.

The Danish physicist Benny Lautrup distinguishes between "real" computer organisms and "virtual" ones. The virtual computer organisms are those designed to be completely dependent on a specific habitat inside the machine -- in games, in cellular automata, or in virtual environments such as the Tierra simulator. The environments for real computer organisms, known as computer viruses, are real computers, real hardware, mainframes, or networks.

Or is the virtual that which could be ? ......

...."Could be !"

If techno-usage stresses the dematerialized, computational capacities of the virtual, the philosophical tradition that passes through Bergson and Deleuze stresses the latent potentialities of the virtual.

Etymologically, virtual means full of virtue, virtue being taken here as the capacity to act.

Virtue / virtual / virtuous (see virtual reality ) Does the etymology of virtue from vir suggest anything?

Read Morevisible/articulable

In Deleuze's analysis of Foucault, the prison defines a place of visibility ("panopticism") and penal law defines a field of articulability (the statements of deliquency). In the same manner, the asylum emerged as a place of visibility of madness, at the same time as medecine formulated basic statements about "folly". (do the two always coincide temporally?)

Read Morevision

Any theory of vision must describe some relation between the eye and the brain. Humberto Maturana studied the visual cortex of the frog and summarized his research in an article entitled, "what the frog's eye tells the frog's brain." Maturana and his co-authors demonstrated that the frog's sensory receptors speak to the brain in a language that is highly processed and species specific. If every species constructs for itself a different world, which is the world? Thus Maturana's credo: There is no observation without an observer.(K. Hayles, "Simulated Nature and Natural Simulations," in Uncommon Ground.) Further research led Maturana to conclude that perception is not fundamentally representational, that the perceiver encounters the world through his own self-organizing processes, through autopoesis.

Read Morevisuality

"Thought is what sees and can be described visually." --René Magritte in a letter to Michel Foucault.

Visuality can be thought of as sight as a social fact, with its historical techniques and discursive determinations. -- as a set of scopic regimes, of which modernity is one example. (see also vision )

Sigmund Freud provides a kind of scientific founding myth for the importance of visuality in human society in his exploration of the upright gait. For Freud, the assumption of the upright gait made man's genitals, which were previously concealed, visible. (Had women's genitals previously been revealed and were now concealed?) This was accompanied by the devaluation of the intermittent olfactory stimulus which the menstrual process produced on the male psyche, in favor of the continuity of sexual excitation, the founding of the family, and the threshold of human civilization. (Civilization and its Discontents, p. 46-7 n.) (see sexuality.)

In The Order of Things, Michel Foucault describes epistèmes as systems of visibilities.

Perspective and Cartesian rationality provided the classical regime of visuality, which was meant to be founded on the geometric certainties of optics.

Read Morevisualization

In The Philosophy of Space and Time, Hans Reichenbach develops the concept of visualization in relation to Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries. Many of his arguments are a critiqe of Kant based on scientific progress since the time of Kant, especially the theory of relativity. (see scientific space )

Read MoreWar

In foraging societies men go to war to get or keep women. Access to women is the limiting factor on male's reproductive success. The most common spoils of tribal warfare are women. Raiders kill the men, abduct the nubile women, gang-rape them, and allocate them as wives. Leaders may sometimes use rape as a terror tactic to attain other ends, but it is effective precisely because the soldiers are so eager to implement it. In fact, it often backfires by giving the defenders an incalculable incentive to fight on, and probably for that reason, more than out of compassion for enemy women, modern armies have outlawed rape. (Pinker, How the Mind Works, p. 513)

Read Morework

In his reassesment of the "hardships" and "poverty" of hunter-gatherer societies, Marshall Sahlins describes the effect of the market-industrial system as instituting scarcity and sentencing us to "life at hard labor." (Stone Age Economics, p.4)

Read Morewriting

Is writing merely a way of recording language by visible marks, or does it have its own linguistic function? Edmund Husserl describes writing as virtual communication. It makes communications possible without immediate or even mediate personal address. By means of writing, the socialization of humanity is elevated to a new stage.

From Assyrian time on, the bulk of writing is in administrative and economic documents, mainly in the form of lists. In referring to the "scriptural economy" Michel De Certeau (The Practice of Everyday Life) points to writing as a "triumphal conquista of the economy, that has, since the beginning of the 'modern age' given itself the name of writing." (p. 131) For de Certeau, the installation of the scriptural apparatus is the triumph of a modern discipline." In modern western culture the practice of writing is a myth which gives symbolic articulation to the Occidental ambition to compose its history, and thus to compose history itself." Here, as elsewhere, de Certeau seeks to find archaic processes of resistance within the discipline itself, in this case, forms of orality, and to rehabilitate reading as a nomadic poaching.

De Certeau describes writing as "the concrete activity that consists in constructing, on its own, blank space (un espace propre ) --the page-- a text that has the power over the exteriority from which it has been isolated." (p. 134)

Read More